In 2016, a single dive into a swimming pool changed Noland Arbaugh’s life forever. At just 22 years old, the accident left him paralyzed from the shoulders down. For years, his world shrank to the confines of his chair, his routines, and the long days of stillness. He could think and speak, but much of his independence, along with his sense of purpose, had vanished.

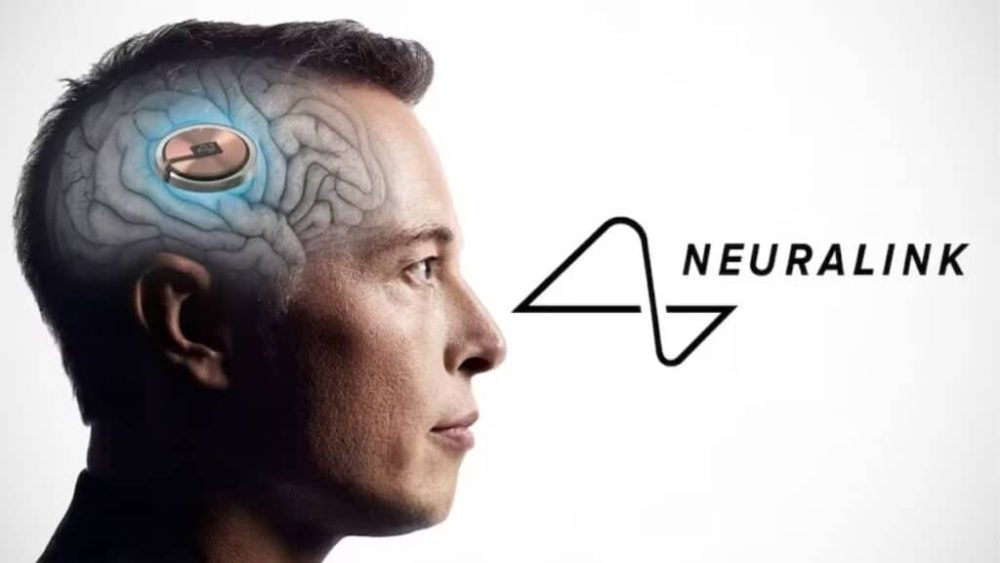

Eight years later, in January 2024, Arbaugh became “Participant One” in Neuralink’s first human trial. A robot delicately stitched 64 superfine threads tipped with over 1,000 electrodes into the motor cortex of his brain. The implant, known as the Link, promised something radical: the ability to control a computer directly with thought.

When Arbaugh revealed his identity on stage at a Neuralink all-hands meeting weeks later, he rolled into the spotlight with a Texas A&M cap, grinned, and greeted the world: “Hello, humans.”

The Present: A Second Life Online

Now 30, Arbaugh describes his brain chip as invisible; he wouldn’t even know it was there if not for the surgery. But the effect on his life is anything but hidden. Within a week of his operation, he was moving a digital cursor with his mind, breaking speed records for brain-computer control.

Two mental strategies allow him to surf the web, text friends, study, and, his favorite pastime, play video games. With “attempted movement,” he imagines moving his paralyzed hand as if gripping a mouse. With “imagined movement,” he envisions the cursor’s path across the screen. Both methods have become second nature.

The Link has given him independence that he once felt lost. Tasks that used to require awkward voice commands or a mouth stick are now seamless. He spends up to ten hours a day using the device, whether playing Civilization VI, taking college classes in neuroscience, or preparing professional talks. “I feel like I’m playing catch-up for eight years of not doing anything,” Arbaugh says.

Not every moment has been smooth. Weeks after the implant, most of the device’s electrodes retracted from his brain tissue, threatening to undo his progress. Engineers scrambled, adjusted algorithms, and restored much of the functionality. Arbaugh, unfazed, framed the setback as part of the experiment: “The whole point of this study was to find out what does and doesn’t work.”

The Future: A Cyborg and Beyond

Eighteen months in, Arbaugh calls himself, half-jokingly, a cyborg. “Technically, I have been enhanced by a machine,” he admits, though he still insists he’s “just a regular guy.” Yet his story represents more than a single medical milestone.

Neuralink’s ambitions extend far beyond moving a cursor. Future trials aim to restore sight, create mind-controlled prosthetics, and even let patients inhabit humanoid robots. Arbaugh himself sees technology, not just biology, as the future of medicine: “I think a lot of disabilities, cures, and answers we’ve been searching for will come through tech. That kind of surprised me.”

The assumptions for the future are bold but tangible. Within the next decade, brain-computer interfaces could rival pacemakers in prevalence, standard medical tools that restore independence. In two decades, they might transcend treatment altogether, enhancing human cognition and bridging the gap between biological and artificial intelligence.

The First Step Into A New Era

For now, Arbaugh is living proof of the possibility. He games with his dad again, studies subjects he once thought closed to him, and speaks to crowds about a future where disability need not mean disconnection.

He is not just the first Neuralink patient; he is the first chapter of a story still being written, a story where science fiction edges closer to daily life.

As Elon Musk quipped during a Neuralink update: “The future is going to be weird, but pretty cool.” Arbaugh’s journey suggests it may also be profoundly human.