For the first time, physicists have visually confirmed one of the most mind-bending predictions of Einstein’s theory of relativity. The Terrell-Penrose effect causes ultra-fast objects to appear not only compressed, but also strangely twisted and rotated. By creatively slowing down light in a laboratory, researchers in Vienna have brought this theoretical illusion to life, revealing how reality distorts at near-light speeds.

The Prediction That Defied Intuition

According to Einstein’s special theory of relativity, when objects approach the speed of light, strange phenomena occur in our perception of them. While it’s known that objects physically contract in their direction of motion (a phenomenon called Lorentz contraction), there’s an additional optical illusion that makes them appear rotated.

“Suppose a rocket whizzes past us at ninety per cent of the speed of light. For us, it no longer has the same length as before it took off, but is 2.3 times shorter,” explains Professor Peter Schattschneider from TU Wien. However, he notes, “this contraction cannot be photographed” because light from different parts of the object reaches our eyes at other times.

This time lag in light arrival creates the Terrell-Penrose effect, named after physicists James Terrell and Roger Penrose, who independently discovered it in 1959. A fast-moving cube wouldn’t just look flattened; it would appear twisted, as if someone had rotated it.

The Laboratory Breakthrough: Slowing Down Light

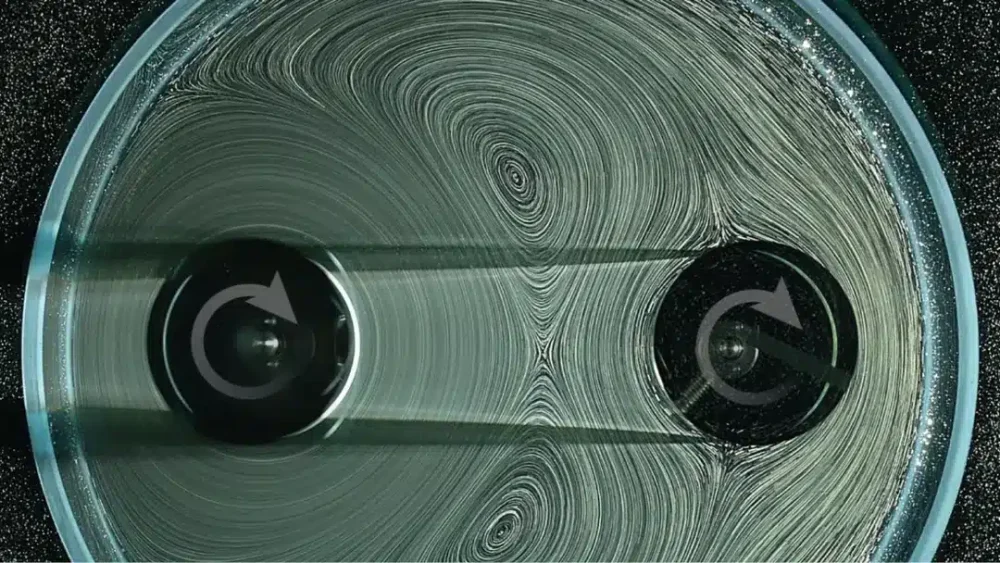

The challenge? We can’t actually accelerate objects to near-light speeds. So, the research team, led by Professor Schattschneider, found an ingenious workaround: they recreated the conditions by effectively slowing down the speed of light to a crawl, just 2 meters per second.

“We moved a cube and a sphere around the lab and used the high-speed camera to record the laser flashes reflected from different points on these objects at different times,” explained students Victoria Helm and Dominik Hornof, who experimented. By carefully timing when different parts of the objects were illuminated, they simulated what would happen if light traveled slowly enough that these relativistic effects became visible at ordinary speeds.

What They Actually Saw

The results were exactly as relativity predicted:

-

A cube appeared twisted and rotated, not just compressed

-

A sphere remained spherical, but its north pole appeared displaced

-

The effects became more dramatic as the simulated speed increased from 80% to 99.9% of light speed

This confirms that our intuitive understanding of how fast-moving objects should look is fundamentally wrong. The combination of actual physical contraction and the different travel times of light creates an illusion that our brains interpret as rotation.

Where Art Meets Science

Remarkably, this scientific breakthrough began as an art-science collaboration. Artist Enar de Dios Rodriguez initially explored the concept of “slow light” through ultra-fast photography in partnership with the University of Vienna and TU Wien. This creative approach ultimately led to the first experimental visualization of an effect that had remained purely theoretical for over 60 years.

The Significance

While we won’t see Formula One cars twisting as they race by anytime soon (the effect only becomes noticeable at significant fractions of the speed of light), this demonstration helps physicists and students alike develop an intuition about relativistic effects. It provides tangible evidence for one of relativity’s most counterintuitive predictions and offers a new way to understand how motion warps our perception of reality.

The research, published in Communications Physics, represents a milestone in making the strange world of high-speed physics visually accessible, proving that sometimes, to see the truth about how the universe works, we need to look beyond what our intuition tells us should be there.

This extraordinary demonstration reminds us that reality, when viewed through the lens of relativity, is far stranger and more wonderful than our everyday experience suggests.